By Dean Murray

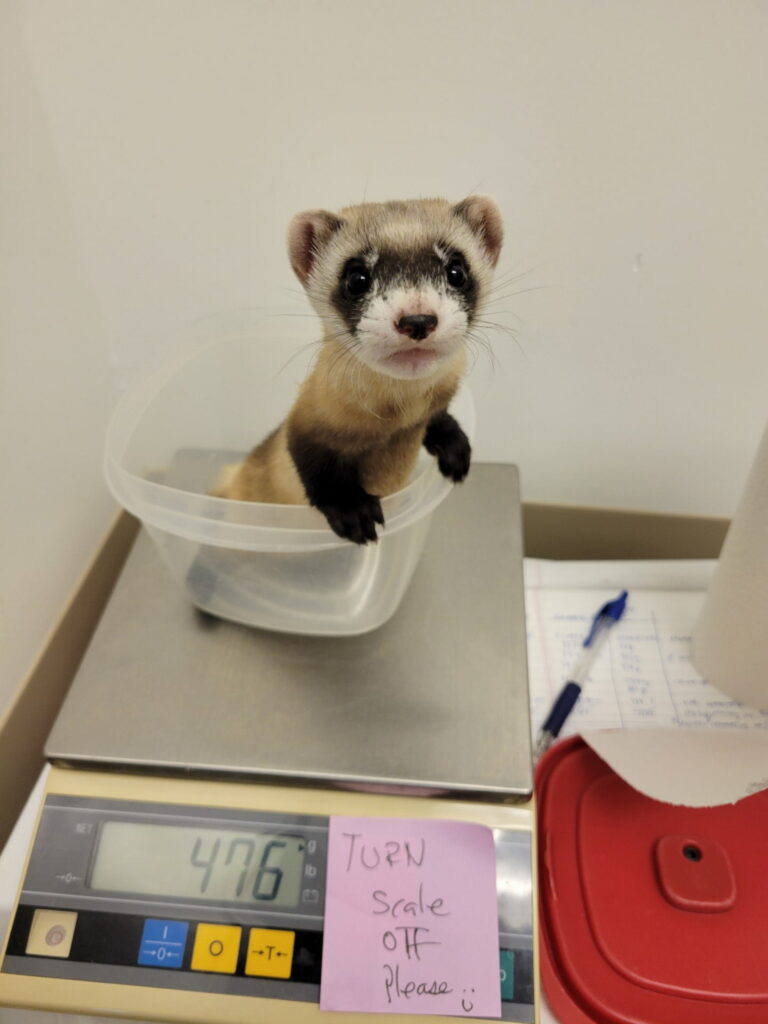

Scientist have cloned two black-footed ferrets to help conserve the endangered critters.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (UFSWS) and its genetic research partners have announced the birth of the ferrets – known as Noreen and Antonia – along with updates on their latest efforts to breed previously cloned black-footed ferret, Elizabeth Ann.

The black-footed ferret is one of North America’s most endangered mammals. Thought to be extinct, captive breeding, habitat protection, reintroductions and cloning have helped restore them to over 300 animals in the wild.

Noreen was born at the National Black-footed Ferret Conservation Center in Colorado, while Antonia resides at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute in Virginia.

UFSWS say: “Both were cloned from the same genetic material as Elizabeth Ann. They are healthy and continue to reach expected developmental and behavioral milestones.”

The Service and its research partners plan to proceed with breeding efforts for Noreen and Antonia once they reach reproductive maturity later this year.

This scientific advancement to clone the first U.S. endangered species is the result of an innovative partnership among the Service and critical species recovery partners and scientists at Revive & Restore, ViaGen Pets & Equine, Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

UFSWS say: “The application of this technology to endangered species addresses specific genetic diversity and disease concerns associated with black-footed ferrets. The Service views this new potential tool as one of many strategies to aid species recovery alongside efforts to address habitat challenges and other barriers to recovery.”

UFSWS say Elizabeth Ann remains healthy at the National Black-footed Ferret Conservation Center in northern Colorado, exhibiting “typical adult ferret behaviour”.

Planned efforts to breed Elizabeth Ann were unsuccessful due to a condition called hydrometra, where the uterine horn fills with fluid.

Her other uterine horn was not fully developed, which UFSWS say is not unusual in other black-footed ferrets and therefore not believed to be linked to cloning.

“Elizabeth Ann otherwise remains in excellent health, symbolizing the early progress in biotechnology for species conservation,” adds UFSWS.

Elizabeth Ann, Noreen and Antonia were cloned from tissue samples collected in 1988 from a black-footed ferret known as Willa and stored at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Frozen Zoo.

All black-footed ferrets alive today, except the three clones, are descendants of the last seven wild individuals. This limited genetic diversity leads to unique challenges for their recovery. Besides genetic bottleneck issues, diseases like sylvatic plague and canine distemper further complicate recovery efforts.

Cloning and related genetic research could offer potential solutions, aiding concurrent work on habitat conservation and reintroducing black-footed ferrets into the wild.

Continuing genetic research for black-footed ferrets includes efforts to breed offspring from Noreen and Antonia, which would significantly increase the species’ genetic diversity.

The UFSWS say collaborative work among partners also aims to achieve other long-term goals, such as developing resistance to sylvatic plague and potentially other diseases.

This is Premium Licensed Content. Would you like to publish this article? Please contact our licensing team.